|

Pears

were introduced to Britain and to the new world from Europe,

principally

France and Italy. Many trees grew in private gardens, and wealthy

individuals

cherished their favourite varieties in the same way that we enjoy fine

wines. Accounts of pear cultivation, and of knowledge of different

varieties

date back to Roman times. (Tacitus)

|

|||

|

The Caillou Rosat (Rosy

pebble) existed

in France before the Conquest, and was a popular variety. It may have

been

so named for its size and shape or for the grit which it contained!

At some time, soon after the Norman Conquest, it was introduced to England. In an England whose ruling classes spoke first French and then eventually a form of English, the spelling and the pronunciation gradually changed, as you will see below. Court accounts during the early years of the reign of Henry III (1207-72) show that pear fruits were being imported from France, and for many years French varieties dominated British orchards. (1) A Wardrobe account for Henry III for 1252 records that a 'Janettar' pear was bought, together with 'Sorelles and Cailloels', both popular pear varieties, from John the Fruiterer of London. (Roach) In 1236, Henry III married Eleanor of Provence, who was a keen gardener, and from this time they developed extensive gardens and orchards. The royal accounts record the purchase of pear trees: |

||

| in 1262, a writ of Henry III directed his gardener to plant six 'Cailhou' pear trees at Westminster and the same variety in the gardens of the Tower. (Close Rolls of the Reign of Henry III) This was the same as the 'Cailloels' recorded earlier, so they must have been well liked by the royal family! | |||

| Edward I, who succeeded his father Henry III as king in 1272, married Eleanor of Castille who was also a keen gardener. She herself created a new garden and planted orchards at Kings Langley in Hertfordshire, bringing gardeners over from Aragon especially to do this work. The accounts of the king for 1276-92 show that young pear trees were produced for the royal gardens at Westminster, the varieties being 'Kaylewell' or 'Calswel', 'Rewel' or 'de Regula' and 'Pesse-pucelle'. 'Kaylewell' was a synonym for 'Caillou', the Burgundy pear which, though a hard, rather inferior fruit only fit for baking, seems to have been the most generally planted in England and was certainly popular with the royal family.The variety was recognized over the next several centuries. In the 1831 a horticulturalist, George Lindley, was writing about Summer Rose, also known as Caillot Rosat pears. He believed they might be the same as the Caillouels mentioned above. (2) |  |

||

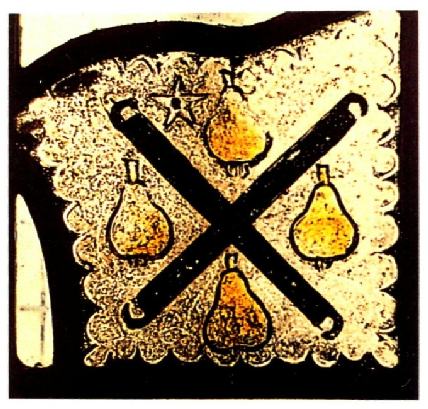

Arms of the Company of Glaziers |

Back in about the Sixteenth Century, members of the Kellaway/Callaway family bore arms. Kellaways were associated with glass-making, probably about the time of the re-building of Sherborne Abbey. The family coat of arms bore a strong resemblance to that of the Worshipful Company of Glaziers and Painters of Glass, arms still visible at their London headquarters today. |  Glass at Sherborne Abbey |

|

|

The Arms contain glaziers’ nippers, or grozing irons, “in saltire” (crossed) and four pears “vert”. The description by the visitor from the College of Arms to Sir John Kellaway (or Callaway) of Hampshire refers specifically to “Kelway pears”. How did this happen? The most likely explanation is this. Heraldic symbols often made puns upon the name of the bearer of the arms. The first armigerous Callaway or Kellaway most probably, while copying from the glaziers’ arms, replaced the nails therein by pears with a name similar to his own. Kelway pears. These arms are recorded at the College of Arms. |

||

| So what of the Caillouet

clan in

all this?

The Kellaway/Callaway hypothesis, which has increasingly sound evidence, is that the name was introduced just after the Norman conquest, by a knight with a name like Caillouet. He may have come from the village near Evreux, which is pronounced Ky-oo-way. The spellings in England, especially in those non-literate and turbulent times, are various. The Caillouet and Cayouette clans in North America are descendants of Gilles of Brest. Gilles Caillouet's descendents, as well as those from the Brest region today, usually pronounce their name Ky-oo-ett. Nevertheless it has been the hope of K/C researchers to demonstrate a link, if it exists, between the Callaways and the Caillouets. Unfortunately, the evidence in France has probably disappeared as a result of the civil unrest at the time of the Revolution, and we may be unable to bridge the centuries between the Normans and Gilles. However there are two interesting facts. In his work on Quebec genealogy, published in 1914 , N-E Dionne (3) made specific allusion to the Normandy village. He also wrote that Caillouet is a “sorte de poire”. (p.101) Unfortunately, Dionne cited no sources. Dionne has been disparaged for the poor quality of his research. However, I must ask: where did he get that idea from? It cannot simply be a coincidence! Has the name been in hiding in French for 900 years? In 1611 the English lexicographer, Randle Cotgrave defined Caillouët as “the name of a very sweet peare”.(4) Cotgrave could conceivably have been Dionne’s source, even over a period of 300 years. And the pear seems to have become sweeter! All this proves nothing of course, but I like to think that it is a contribution to the discussion, and may lead to a breakthough in the future. Bibliography |

|||

| Links: Return to Kellaway | The mystery of Caillouet |

Email me on bill@kellaway.info |

|

|

|||